Boosted by a call from U.S. President Barack Obama on Thursday, the acting prime minister of Ethiopia, Hailemariam Desalegn, is taking steps to assert his authority, according to Ethiopian Review sources in Addis Ababa.

The ruling TPLF junta is intending to make Hailemariam a figurehead prime minister. The real power still rests solidly in the hands of Seyoum Mesfin and the TPLF Politburo. However, Hailemariam is encouraged by the U.S and European governments, as well as his own supporters, to start exercising real authority even before the rubber-stamp parliament formally appoints him as prime minister.

Hailemariam’s real challenge to his authority as prime minister comes from none other than the wife of the late dictator Meles Zenawi.

According to Ethiopian Review sources, Azeb Mesfin is organizing discontented TPLF member against the acting prime minister, paving the way for herself to assume that position. It is Azeb who pushed the date when Hailemariam to be formally appointed as prime minister until after the burial of Meles Zenawi on September 2.

Concerned by growing opposition within the TPLF rank, Hailemariam has beefed up security around him, and the U.S. Gov’t has promised to provide him additional security. It is reported on Friday that U.S. security specialists on contract from the Africom have started to provide Hailemariam with intelligence and advise on how to protect against possible coup d’etat.

Hailemariam is also secretly reaching out to Ethiopian opposition groups. His communication with at least two opposition leaders was leaked to the VOA on Friday by a faction in the TPLF that opposes Hailemariam.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The Obama Administration continues to push the TPLF junta to accept Hailemariam Desalegn as the new “prime minister.” President Obama’s call to Hailemariam yesterday was part of the U.S. effort to strengthen Hailemariam’s position. However, the mid- and lower-ranking TPLF members are revolting against the decision to make Hailemariam the new prime minister, fearing that power could slip away from them.

U.S. President hold talks with Ethiopia’s new leader

ADDIS ABABA (AFP) — Ethiopia’s new leader Hailemariam Desalegn, expected to assume power following the death of the country’s longtime prime minister dictator, readied for the post Friday after holding talks with US President Barack Obama.

But Hailemariam, 47, a relatively little known politician overshadowed by his mentor Meles Zenawi, who died on Monday, faces tough challenges both internally and across the wider volatile Horn of Africa region.

Obama, who telephoned Hailemariam late Thursday, urged him to “use his leadership to enhance the Ethiopian government’s support for development, democracy, human rights and regional security,” the White House said.

Hailemariam has also met with South Sudan’s foreign minister and his Kenyan counterpart, who were in Addis Ababa on Thursday to pay their respects to Meles, who died aged 57 after a long illness.

Official mourning continues for Meles, with crowds gathering for a third day in the grounds of the National Palace, where photos of the late leader are on display.

Scores of police and army officers alongside ordinary citizens, many weeping loudly, have gathered to pay their respects ever since his body was flown home following his death in a Brussels hospital.

But the political process continues behind doors. Government spokesman Bereket Simon has said Hailemariam is expected to be formally sworn in in a emergency parliament session at “any time.”

In a rare peaceful handover of power in Ethiopian history, former water engineer Hailemariam took over as interim leader on the death of Meles, who had ruled with an iron-fist since toppling dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1991.

A close ally of Meles as deputy prime minister and foreign minister since 2010, Hailemariam was elected deputy chair of the ruling coalition Ethiopian Peoples’ Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) after the party’s fourth win, a landslide victory in 2010.

In a country long dominated by the major ethnic groups — most recently the Tigray people, like Meles — Hailemariam notably comes from the minority Wolayta people, from the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples Region.

He served as president for the region — the most populous of Ethiopia’s nine ethnic regions — for five years.

But within the coalition, some of the most influential figures hail from the northern Tigray region, members of Meles’s ex-rebel turned political party, the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF).

Seen as a figurehead

Analysts have suggested that several others are still jostling for power behind doors in the often secretive leadership, even if in the open they may not take part in the running for the top job.

“Many see him as a figurehead, part of a gesture by Meles and the ethnic Tigrayans to give more prominence to other ethnic groups,” said Jason Mosley of Britain’s Chatham House think-tank.

He is also a Protestant, unlike the majority of Ethiopia’s Christians, who follow Orthodox traditions.

But others less critical warn that while outside the Tigray power base, that could in fact be a strength.

“His ethnicity is considered an advantage, because it is a minority in a multi-ethnic region and, most importantly, not from the numerically dominant Oromo or Amhara,” the International Crisis Group said in a recent report.

Critics also point to his relatively young age, lack of experience and the fact he was not part of the rebel movement which toppled Mengistu, unlike many in the ruling elite.

Instead, Hailemariam, who studied civil engineering in Addis Ababa, was completing his masters degree at Finland’s Tampere University when Mengistu fell.

Hailemariam, while a protege of Meles, is therefore seen as an outsider by some.

“He is a political novice, he has not been part of the old guard, he has not been in the bushes fighting with the rebels,” Berhanu Nega, an exiled opposition leader and former mayor of Addis Ababa, told the BBC.

“He is a Medvedev for a group of Putins in the ruling party with their own internal squabbles,” he added, drawing parallels with Russian political dynamics.

The government however has insisted Hailemariam will remain in the post until elections due in 2015, although he must first be formally chosen as head of the ruling EPRDF party, likely later this year.

“The secession issue has been settled for good,” said spokesman Bereket.

The Economist

THE death of Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia’s prime minister dictator, on August 20th reveals much about the country he created. Details of his ill health remained a secret until the end. A short broadcast on state television, late by a day, informed Ethiopians that their “visionary leader” of the past 21 years was gone. He died of an unspecified “sudden infection” somewhere abroad. No further information was given. In the two months since the prime minister’s last public appearance the only local Ethiopian newspaper that reported his illness was pulped, its office closed, and its editor arrested. Further details of Mr Meles’s death surfaced only when an EU official confirmed that he died in a Brussels hospital.

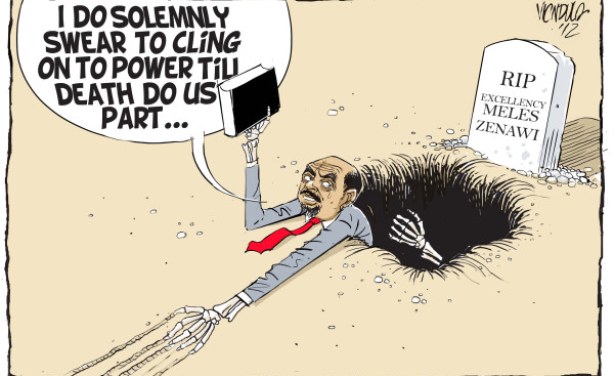

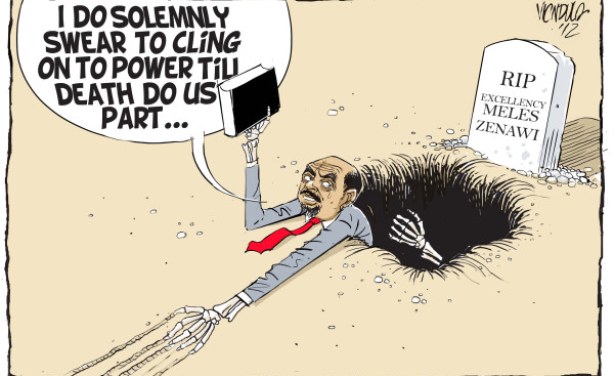

A towering figure on Africa’s political scene, he leaves much uncertainty in his wake. Ethiopia, where power has changed hands only three times since the second world war, always by force, now faces a tricky transition period. Mr Meles’s chosen successor is a placeholder at best. Most Ethiopians, whatever they thought of their prime minister the dictator, assumed he would be around to manage the succession. Instead he disappeared as unexpectedly as he had arrived. He was a young medical student in the 1970s when he joined the fight against the Derg, the Marxist junta that then ruled Ethiopia. He went into the bush as Legesse Zenawi and emerged as “Meles”—a nom de guerre he had taken in tribute to a murdered comrade.

Who exactly was he? As leader of the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front, an ethnic militia from the country’s north, he presented himself to his countrymen as a severe, ruthless revolutionary; yet Westerners who spoke to him in his mountain hideouts found a clever, understated man who laid out, in precise English, plans to reform a feudal state. In 1991, after the fall of the last Derg leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, the 36-year-old Mr Meles (pictured above) took power, becoming Africa’s youngest leader. He had moral authority as a survivor of various famines. Western governments and publics, who became aware of Ethiopian hunger through the Band Aid and Live Aid charity concerts, gave freely. Mr Meles was often able to dictate terms under which donors could operate in Ethiopia and turned his country into Africa’s biggest aid recipient.

Where others wasted development aid, Ethiopia put it to work. Over the past decade GDP has grown by 10.6% a year, according to the World Bank, double the average in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa [false]. The share of Ethiopians living in extreme poverty—those on less than 60 cents a day—has fallen from 45% when Mr Meles took power to just under 30%. Lacking large-scale natural resources, the government has boosted manufacturing and agriculture. Exports have risen sharply. A string of hydroelectric dams now under construction is expected to give the economy a further boost in the coming years.

The flipside of the Meles record is authoritarianism. Before his departure he ensured that meaningful opposition was “already dead”, says Zerihun Tesfaye, a human-rights activist. The ruling party controls all but one of the seats in parliament, after claiming 99.6% of the vote in the 2010 elections. It abandoned a brief flirtation with more open politics after a vote five years previously, when the opposition did better than expected. The regime subsequently rewired the state from the village up, dismantling independent organisations from teachers’ unions to human-rights groups and binding foreign-financed programmes with tight new rules. Opposition parties were banned and their leaders jailed or driven into exile; the press was muzzled.

Internationally, Mr Meles made friends with America, allowing it to base unarmed armed drones at a remote airfield. He also liked to act as a regional policeman. His troops repeatedly entered neighboring Somalia (they are slowly handing over conquered territory to an African Union peacekeeping force). Hostilities have at times flared along the border with Eritrea. Mr Meles cowed his smaller neighbour and persuaded the world to see it as a rogue state. This in turn helped him restrain nationalists at home. In his absence, hardliners on both sides may reach for arms once again.

The nature of power in Mr Meles’s Ethiopia has remained surprisingly opaque. On the surface, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front is a broad grouping encompassing all of the country’s ethnic factions. Like the liberal constitution, it is largely a sham. Real power rests with an inner circle of Mr Meles’s comrades. They all come from his home area, Tigray, which accounts for only 7% of Ethiopia’s 82m people. His acting successor is an exception. HaileMariam Desalegn, the foreign minister, is from the south. His prominence raises hopes that the long dominance of the

The nature of power in Mr Meles’s Ethiopia has remained surprisingly opaque. On the surface, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front is a broad grouping encompassing all of the country’s ethnic factions. Like the liberal constitution, it is largely a sham. Real power rests with an inner circle of Mr Meles’s comrades. They all come from his home area, Tigray, which accounts for only 7% of Ethiopia’s 82m people. His acting successor is an exception. HaileMariam Desalegn, the foreign minister, is from the south. His prominence raises hopes that the long dominance of the Habesha, the Christian highlanders of the Amhara and Tigray regions, may be diluted. But few think he has enough standing to exert real control.

Power will be wielded by Tigrayans such as Getachew Assefa, the head of the intelligence service; Abay Tsehaye, the director-general of the Ethiopian sugar corporation; and Mr Meles’s widow, Azeb Mesfin. An MP, she heads a sprawling conglomerate known as EFFORT, which began as a reconstruction fund for Tigray but now has a host of investments. It is unclear whether any of the Tigrayans will seek the leadership of the ruling party or be content to wield control from the sidelines. A struggle among this elite would be a big threat to stability.

* Meles died Monday of liver cancer

* In Ethiopia, Feteh editor jailed during trial

Ethiopian authorities must immediately release Temesghen Desalegn, editor of the leading weekly Feteh, who was ordered jailed today pending his trial on defamation, the Committee to Protect Journalists said today.

The High Court judge deemed Temesghen a flight risk during his trial, which resumes on September 3, according to local journalists. Police summoned the journalist for questioning on August 1 and told him they were charging him over his articles published in seven editions of the weekly Feteh that were critical of the administration of the late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, local journalists said. Mastewal Publishing and Advertising PLC, the company that publishes Feteh, has also been charged, the same sources said.

Temesghen is being held at Kality Prison in Addis Ababa, the capital, local journalists said. Feteh has not been published since July 20, when the Ministry of Justice blocked the sale and distribution of 30,000 copies to suppress the paper’s coverage concerning the health of Meles, the sources said. Meles died Monday of liver cancer, according to international news reports… [read more]

The rubber-stamp parliament in Ethiopia was scheduled to meet today to formally appoint Hailemariam Dessalegn as prime minister, but Ethiopian Review sources in Addis Ababa reported this afternoon that the meeting was abruptly canceled yesterday after Meles Zenawi’s wife Azeb Mesfin refused to leave the prime minister’s house. The mother of corruption dared any one to even suggest that she vacates “her house” until her husband is buried on September 2.

On top of that, it is reported that mid-ranking TPLF members have been confronting Seyoum Mesfin and other senior TPLF leaders since Tuesday over the selection of Hailemariam. Their complaint is that a position as critical as the prime minister should be reserved for the Tigray People’s Liberation Front. Our sources are reporting that Azeb Mesfin is behind the simmering revolt in the TPLF rank. A deadly clash among the various TPLF factions is becoming a real possibility.

The nature of power in Mr Meles’s Ethiopia has remained surprisingly opaque. On the surface, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front is a broad grouping encompassing all of the country’s ethnic factions. Like the liberal constitution, it is largely a sham. Real power rests with an inner circle of Mr Meles’s comrades. They all come from his home area, Tigray, which accounts for only 7% of Ethiopia’s 82m people. His acting successor is an exception. HaileMariam Desalegn, the foreign minister, is from the south. His prominence raises hopes that the long dominance of the

The nature of power in Mr Meles’s Ethiopia has remained surprisingly opaque. On the surface, the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front is a broad grouping encompassing all of the country’s ethnic factions. Like the liberal constitution, it is largely a sham. Real power rests with an inner circle of Mr Meles’s comrades. They all come from his home area, Tigray, which accounts for only 7% of Ethiopia’s 82m people. His acting successor is an exception. HaileMariam Desalegn, the foreign minister, is from the south. His prominence raises hopes that the long dominance of the